What's Testicular cancer

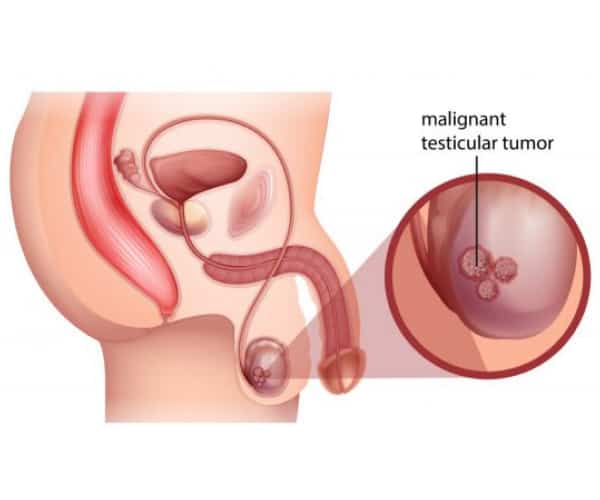

Testicular cancer is male cancer in which cancer cells form from the tissues of one or both testicles. The testicles are the organs in which spermatozoa and some male hormones form in men (they function like the ovaries in women).

The testicles are two in the scrotum, a bag of skin located directly under the penis. Usually, the tumour affects only one testicle. Still, men who have already had this tumour in the past have a higher risk of developing the same tumour in the other testicle.

How widespread is it

In 2022, 2,300 new testicular cancer diagnoses are expected, especially among the young population: it is, in fact, the most common cancer in the age group between 15 and 40 years, while it is scarce that it occurs after the age of 60.

The 5-year survival from diagnosis is about 91 per cent overall. Still, the strategies implemented to diagnose it as soon as possible, and the possibility of intervening with multidisciplinary treatments offered by high-specialized centres, have made it possible to achieve very curability rates and elevated: 99 per cent if the disease is discovered early, 90 per cent if there is the involvement of the abdominal lymph nodes and more than 80 per cent in cases of lung, liver and bone metastases. As for the prevalence, about 63,400 men live in Italy after a diagnosis of testicular cancer.

Testicular cancer causes remain undetermined, although several risk factors may favour it. Among these, the main one is cryptorchidism, the failure to descend into the scrotum of one of the testicles, which remains in the abdomen or groin. This condition increases the chances of malignant transformation of cells up to 10 times compared to the general population, with a variable risk depending on the location of the cryptorchidism: high if the testicle is in the abdomen and lower if it is in the groin. The odds are further reduced if the abnormality is surgically corrected before six. The paediatrician must explain to parents that cryptorchidism still represents an increased risk for this tumour so that the child, once grown, is aware of it and regularly performs testicular self-examination once a month to facilitate diagnosis early in case of cancer.

Another important risk factor is Klinefelter's syndrome due to chromosome abnormality. Finally, men with testicular cancer have a 20-50 times higher risk of developing same cancer in the other testicle.

The following should also be considered: a positive family history of this cancer, exposure to substances that interfere with endocrine balance (for example, occupational and ongoing exposure to pesticides), infertility (sterile men have a risk of developing cancer three times higher than infertile men) and smoking.

There is not a single testicular tumour.

- Seminomas represent about half of the cases and are the forms with the most favourable course. They consist in the malignant transformation of germ cells, that is, those that give rise to spermatozoa; they are the most frequent testicular tumours in the fourth decade of life and are often associated with a variant that also involves non-seminal cells (in this case we speak of mixed germ forms).

- Non-seminomas: they include different forms, including embryonic carcinomas, choriocarcinomas, teratomas and tumours of the yolk sac, that part associated with the embryo that contains reserve material for its nourishment.

Cancer usually begins with a lump, enlargement, swelling, or feeling of heaviness in the testicle. The sudden onset of acute testicular pain is also typical of this tumour, along with a rapid increase in organ volume caused by bleeding. Therefore, men need to learn to self-examine the testicle (just as women do a self-examination of the breast) by palpating the organ from time to time to discover any abnormalities. Another symptom not to be overlooked is the shrinking of the testicle, which can signify the onset of the disease.

There are no organised prevention programs for testicular cancers. The same tumour markers, such as alpha-fetus protein and beta-HCG (substances that can be found in the blood in this type of cancer), help confirm the diagnosis and follow the evolution of the disease over time and are not needed for early diagnosis. However, given the young age of the population at risk, the importance of self-examination of the testis should be emphasised, with attention to any modification of the anatomy or shape of the scrotum. Adults and teens should know the size and appearance of their testicles by examining them at least once every 30 days after a warm bath, i.e., with the scrotal sac relaxed. Each testicle should be examined by rotating it between the thumb and forefinger for abnormal lumps, which the doctor should review immediately. This habit can allow for early diagnosis. It is essential to teach children this manoeuvre because the testicles exam provided in the past for compulsory military service is no longer carried out after the abolition of the draft.

After the physical examination by the specialist, the diagnosis of the tumour is carried out using a testicular ultrasound and a Doppler ultrasound to assess the extent of the lesion and differentiate cancer from benign lesions such as cysts. In addition to these tests, some markers are measured, i.e., substances in the blood produced by tumour cells or induced by the presence of the tumour.

These markers are alpha-fetus protein (αFP), beta-HCG (βHCG) and lactic dehydrogenase (LDH). In case of suspected positivity, surgery is carried out with a small incision in the groin to remove the lesion, often studied during the operation. If there is confirmation that it is a tumour, proceed immediately with the excision of the testicle. Subsequently, a thorough histological examination establishes the characteristics of cancer.

The patient undergoes further investigations, such as CT of the chest and abdomen, to check for metastases or if some cancer cells have spread to other body parts. The multidisciplinary team will establish specific treatments for the individual patient based on the results.

Evolution

Testicular cancer is classified into the following stages:

- stage I, with tumour confined to the testicle;

- stage II, with cancer spreading to the lymph nodes of the abdomen;

- Stage III is when cancer has spread beyond the lymph nodes, even with distant metastases in organs such as the lungs and liver.

The therapies

The treatments available vary differing on the type and extent of cancer. The finding of tumour markers (αFP, βHCG and LDH) is essential not only, as we have seen, for diagnosis but also treatment because it allows you to establish the most suitable therapy for each case and monitor its effectiveness.

The patient with testicular cancer may have fertility problems and should be advised that he can preserve it by storing semen samples collected before surgery in a sperm bank.

For several cases where the cancer is diagnosed when it is still in its early stage, testicular removal surgery may be the only treatment needed, followed by active surveillance consisting of blood checks and ultrasound investigations. Technically, the operation is called orchiectomy; it is performed through an inguinal incision and involves the removal of the testicle, epididymis and spermatic cord with their respective blood vessels. And radiographic over time.

After removing the testicle, during the same operation or later, a silicone prosthesis is inserted (like the testicle inconsistency, shape and size), which allows for maintaining the aesthetic appearance of the scrotum. If cancer has spread beyond the testicles, a second surgery will be required. Abdominal lymph node removal surgery may be used if the tumour has reached the lymph nodes. In other cases, chemotherapy and radiotherapy are associated with surgery.

Chemotherapy. The use of chemotherapy depends on the type of tumour, size and stage; both seminomas and non-seminomas respond particularly well to chemotherapy, a treatment that has radically changed the prospects for survival in these previously often incurable types of cancer. It can be given to prevent relapses (precautionary chemotherapy) and when other organs are involved at a distance.

Radiotherapy. It is particularly effective in seminomas; non-seminoma forms are not sensitive to this type of treatment.