Shock for Chronic prostatitis

Low-intensity extracorporeal shockwave for chronic prostatitis and male chronic pelvic pain

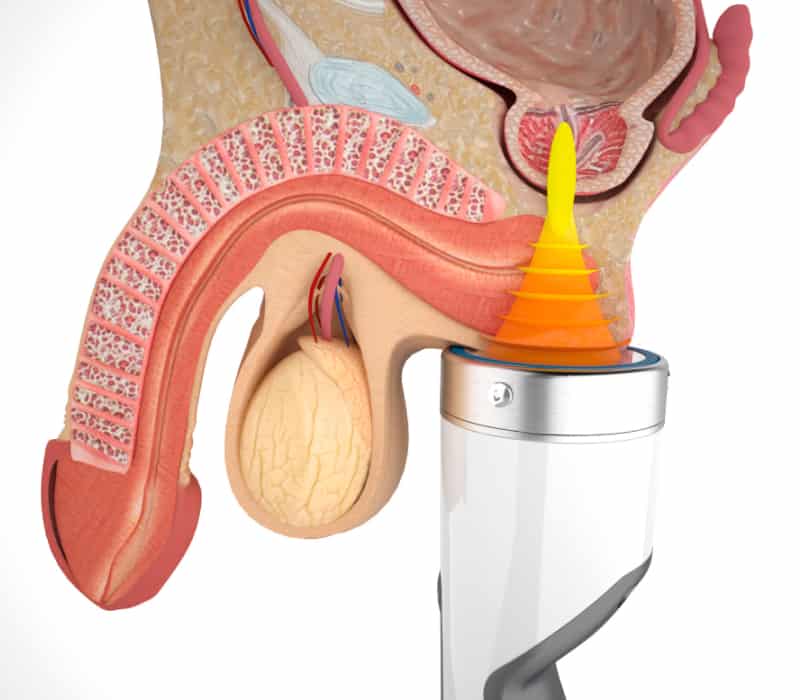

Low-intensity extracorporeal shockwave therapy (LI-ESWT) is a good option for treating male pelvic pain syndrome owing to the simplicity of its application and the lack of any appreciable side effects.

Use of LI-ESWT can enable rapid, minimally invasive outpatient management without contraindications and is, therefore, an attractive technique for many patients.

Prostatitis describes a combination of infectious diseases (acute and chronic bacterial prostatitis), CPPS, or asymptomatic prostatitis.

The NIH classification of prostatitis syndromes includes

- Category I: Acute bacterial prostatitis. Characterized by sudden fever, perineal and suprapubic pain and voiding symptoms. Urine shows signs of urinary tract infection.

- Category II: Chronic bacterial prostatitis. Characterized by symptoms for >3 months with recurrent bacterial urinary tract infection

- Category III: Chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS). Characterized by pain and voiding symptoms for >3 months without detecting bacterial pathogens using standard microbiological methods. CPPS is divided into two subcategories:

- Category IIIA: Inflammatory CPPS. White blood cells are present in prostate fluid, urine, and seminal fluid.

- Category IIIB: Non-inflammatory CPPS. No white blood cells in prostate fluid, urine, or seminal fluid.

- Category IV: Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis.

The incidence of male chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS or prostatitis) has increased significantly in recent decades. An incidence of 5% was estimated in the old series, but studies revealed an incidence of around 15%. The vast majority of male patients are diagnosed with the non-bacterial subtypes. The disease is associated with considerable morbidity with functional limitation and diffuse perineal pain sensations in the prostate, testicles, groin, back and suprapubic region.

CPPS symptoms, such as disturbances of micturition and erectile function (EF), can substantially diminish the quality of life, and can be even more disruptive than the pain. The pathophysiology of CPPS is poorly understood, but is thought to be associated with previous infections, hypercontractility of the pelvic floor, local chemical alterations, and blood perfusion alterations. Women can also develop CPPS symptoms, which can be associated with dyspareunia and/or vaginismus, and which require more complex management of the symptom and the associated factors. Neurobiological and psychological factors could play a more significant role in CPPS in women than in men.

Autoimmune prostatitis has been shown to induce long-lasting pelvic pain in an animal model ,the origin of which could be traced to the prostate. Prolonged contraction of the smooth muscle of the bladder and prostate resulting from activation of a1-adrenergic receptors (a1-ADR) can aggravate the symptoms and discovery of the presence of nanobacteria in patients with CPPS-type prostatitis has suggested novel potential aetiological factors.

According to the NIH classification, CPPS type III B is characterized by a lack of signs of infection in the urine and sperm. The routine procedures required to diagnose type III B CPPS are debatable; instead presence of specific symptoms, signs, and microbiological findings make the clinical diagnosis of CPPS, and the exclusion of more severe diseases is of paramount importance. CPPS can present like a myofascial pain syndrome or involve neurological components, leading to dysfunction of voiding and sexual function. Many of the symptoms are associated with so-called muscular trigger points in the pelvic muscles, which are thickened and sore points, usually within a contracted muscle and are also known as ‘muscle spasms’.

The skeletal muscles of the pelvic floor support and surround the bladder, prostate and rectum. Just like spasms of the neck and shoulder muscles can lead to tension headache, spasms of the pelvic floor can lead to genital pain and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Pain can be felt in the penis, testicles, perineum (sometimes described like the sensation of "sitting on a golf ball"), lower abdomen and lower back. Men sometimes have postejaculatory pain and erectile dysfunction. Indeed, > 50% with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) and patients with interstitial cystitis have pelvic floor spasms on examination, which can be an independent driver of their ongoing symptoms.

The diagnosis is not difficult but does require a slight modification of the regular digital rectal examination. In men, the pelvic floor muscles can be palpated anteriorly to either side of the prostate and laterally during the rectal exam.

Pelvic floor spasm is felt like tight muscle bands, and trigger points as knots of muscle that are often painful on palpation, which usually causes emergence of the patient's symptoms. Indeed, we believe that a common cause of misdiagnosis of prostatitis comes from pain experienced during the rectal exam that is assumed to be due to the prostate but is actually caused by palpation of extraprostatic muscles.

Currently, no standardized treatment is available for CP/CPPS. Various agents, such as analgesics, anti-inflammatories, antibiotics, 5a-reductase inhibitors, and alpha-receptor blockers, are used individually or in combination. A specific group of patients can find benefit from treatment with an alpha-blocker, whereas the use of antibiotics, although widespread, has no scientific basis. Side effects can outweigh the possible advantages of treatment, reducing the benefit to the patient and leading to discontinuation of treatment.

Physiotherapy, massage, electromagnetic wave therapy, and acupuncture have all been used to treat CPPS. and shockwaves began to be used ~10 years ago. Thus, a decade of scientific evidence is available to support the effectiveness of the procedure. Shock waves can be easily applied perineally without side effects, improving the symptoms related to CPPS, particularly pain, via the resolution of muscle trigger points, in a process called trigger point shockwave therapy (TPST).

Trigger point shockwave therapy (TPST)

Trigger points are thickened and sore spots usually found within a contracted muscle. Thus, trigger-point-focused shockwave therapy (TPST) is a very effective non-invasive treatment for chronic pain in the musculoskeletal system. Focused extracorporeal shock waves enable precise diagnosis and therapy of active and latent triggers.

Shockwave therapy for pelvic pain

ESWT protocols aim to resolve pelvic muscle pain. As well as reducing pain, the shockwaves have an anti-inflammatory action, enabling recovery of the normal function of the pelvic muscles and improving erectile function.

What are shockwaves?

Shockwaves are pressure waves that are concentrated toward a defined focal volume, and which are used at high energy for crushing renal and kidney stones in urology.

Mechanisms of action

When they pass through a fluid, shockwaves generate pressure differences that cause the formation of bubbles (a process known as ‘cavitation’). When these bubbles are hit by a subsequent shock wave, they are deformed until they implode.

This phenomenon enhances the mechanical effect of the shock wave by creating micro-lesions, the magnitude of which is a function of the number of pulses and their energy. In bones, an osteogenetic (generation of bone) response and a vascular response have been observed, whereas in soft tissues, a vascular and anti-inflammatory response are seen.

An immediate vascular response can be linked to the phenomenon of temporary inhibition of the sympathetic nerve endings in the penis with the consequent opening of the capillary bed (known as a ‘wash out’ effect).

The observed anti-inflammatory response is linked to the intense tissue lavage of the wash-out effect, which removes molecules with quinine-like and histamine-like activity present in the region of inflammation. After a few days, this initial response is followed by a second response linked to the increase in the angiogenesis . These effects lead to rapid restoration of joint mobility. The changes in cell permeability and the direct temporary influence on nociceptors also reduce the pain associated with the disorder.

The London Centre for Male Chronic Pelvic Pain syndrome is devoted to researching and treating pelvic pain syndromes in men using the Castiglione–De Oliviera Protocol. Pelvic pain syndromes treated in our centre include prostatitis, pelvic floor dysfunction, elevator ani syndrome, chronic pelvic pain syndrome, and chronic abacterial prostatitis, among other diagnoses.

The protocol was developed by andrologist Dr Fabio Castiglione and physiotherapist André de Oliveira, who is the Director of the Alo Physiotherapy clinic in central London.